Stalking Stokowski

Once upon a time, an American record company

got its hands on some rare and wonderful

Brazilian music and made it even rarer.

This is the story of my hunt for Native Brazilian Music.February 2000

Villa-Lobos (right) introduces Donga (left) to Stokowski

(O Globo, 8 August 1940)I. Allegro brillante: Rio de Janeiro, 1940

In the summer of 1940, Hitler was in command of most of western Europe. Germany seized Norway and Denmark in April. By May, the Wehrmacht had swept over Holland and Belgium in a Blitzkrieg campaign and was proceeding around France’s Maginot Line to trap Allied troops at Dunkirk. France surrendered on 22 June 1940, and Hitler marched triumphantly into Paris. The British were forced to withdraw from Continental Europe. A Nazi invasion of England was imminent.

The United States had not yet entered the war but was keenly desirous to ensure that its southern neighbors refrain from aligning themselves with Germany. The latter was a very real possibility, as Brazilian president Getúlio Vargas had been flirting with fascism since he established his Estado Novo dictatorship in 1937. Vargas even sent a “present” to Hitler: Olga Benário Prestes, Communist revolutionary and the wife of Brazilian Communist leader Luiz Carlos Prestes. A German-born Jewess and seven months pregnant at the time of her deportation, Olga gave birth in a concentration camp, where she died in a gas chamber.

Presiding over a neutral power, his hands tied by an isolationist congress, Roosevelt had few courses of action open to him. (Brazil and the United States did not sign a military accord until May 1942, and it wasn’t until August 1942—after five Brazilian ships had been torpedoed by German submarines a few miles from the Brazilian coast—that Brazil declared war on Germany and Italy.) One thing the President could do was to activate the “good neighbor” policy introduced in his first inaugural address in 1933.

The U.S. Good Neighbor policy manifested itself in various ways, one of them being cultural. The best-known American cultural missions to Brazil were made by Walt Disney in 1941 and by Orson Welles in 1942. While in Brazil, Disney discovered Ary Barroso’s samba “Aquarela do Brasil” and included it—now titled “Brazil”—in his animated film Saludos Amigos (1942), propelling the song to international fame. A second Disney film that owes its existence to the Good Neighbor policy is The Three Caballeros (1944), which did the same for another Ary Barroso song, “Na Baixa do Sapateiro” (renamed “Bahia”). Both films (and a third called Melody Time) featured the animated talking parrot Zé Carioca, a malandro figure based on the real musician José do Patrocínio Oliveira (1904–1987), who participated in several feature films as a member of Carmen Miranda’s band and released some albums as Zé Carioca.

Orson Welles’ Good Neighbor mission was less successful. At the instigation of Nelson Rockefeller and John Hay Whitney, he went to Brazil in 1942 to make an anthological film “especially for Americans in all the Americas” and titled It’s All True. With no script in hand (and perhaps with too much input from countless American and Brazilian functionaries), Welles spent close to six months and a great deal of money improvising his way through the film. He delved into the samba world for the episode Carnival in Rio and reportedly spared no expense in his quest for the authentic. Sambista Raul Marques (1913–1991) told how, during the filming of a batucada, the pernada tripping contest turned violent, but the director egged the contestants on and continued shooting until the bitter end. Several participants were injured, and the actor-singer-songwriter Grande Otelo was hospitalized. When people complained of the violence, Welles said, “I’ll pay for everything.”

Tragedy dogged the production almost from the start. The second episode Welles was directing, Four Men on a Raft, focused on a celebrated 1,650-mile jangada voyage made by four fishermen from Ceará in the northeast to the then federal capital, Rio de Janeiro, with the object of calling Vargas’ attention to their miserable living and working conditions and pleading for government benefits. Welles re-created the voyage with the jangadeiros playing themselves, but during the shooting their leader, Jacaré, drowned when the craft overturned in Guanabara Bay. The same day, Welles’ studio, RKO, pulled the plug on his budget and ordered him home. Welles struggled on with a skeleton crew and eventually shot a silent, black-and-white documentary-style story. Owing to studio conflicts, he was never allowed to finish It’s All True. (For a long time it was believed that the film had been lost. Then, shortly before Welles’ death in 1985, some footage was found in the Paramount vault. Eventually it was edited and released as a documentary in 1993.) Moreover, while in Brazil, Welles was unable to oversee final cuts of his second feature film, The Magnificent Ambersons. That film ended up badly butchered in the cutting room. Welles’ career, at its all-time peak before the Brazilian interlude, suffered a blow from which it would never fully recover.

Playbill from the AAYO’s Buenos Aires concert of 22 August 1940 (image courtesy of the Otto E. Albrecht Music Library, University of Pennsylvania)

But before Walt Disney and Orson Welles, Brazil got Leopold Stokowski. From 1912 to 1938, Stokowski (1882–1977) had been the music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra, where he made his reputation as a showman. To movie-going audiences, the maestro was better known for his participation in the films The Big Broadcast of 1937 (1936), with Jack Benny, George Burns, Benny Goodman, and harmonica player Larry Adler; One Hundred Men and a Girl (1937), with Deanna Durbin and Adolphe Menjou; and above all Disney’s ground-breaking Fantasia (1940). In the gossip columns, the conductor was chiefly recognized for his multiple marriages (one to heiress Gloria Vanderbilt) and for having been Greta Garbo’s lover. Stokowski founded several orchestras, including the All-American Youth Orchestra (AAYO), which he conducted in concerts and recordings during 1940 and 1941. It was this orchestra that in the summer of 1940 sailed with him on board the S.S. Uruguay for a Good Neighbor tour of Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and a few Central American countries. Their first port of call was Rio de Janeiro, where they played concerts at the magnificent Teatro Municipal on the evenings of 7 and 8 August.

Stokowski was a self-professed aficionado of Brazilian music. Prior to sailing, he wrote to the Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos, whose works he’d been championing since 1927, and solicited his help in collecting and recording “the most legitimate popular Brazilian music.” The maestro explained that because of his great interest in the music of Brazil, he would pay all expenses involved and even specified the types of music desired: sambas, batucadas, marchas de rancho, macumba, emboladas, etc. The proposed recordings were intended for release by Columbia Records. They were also to be played at an upcoming Pan-American folkloric congress (which never took place).

Villa-Lobos complied with the conductor’s request (see his letter to Stokowski) and turned for help to his friends, the sambistas Donga, Cartola, and Zé Espinguela, who rounded up the cream of Rio’s musicians. Perhaps only a man of Villa-Lobos’ stature and his close connections to the choro and samba worlds could have assembled such a dream team for Stokowski. Indeed, any poster announcing the following lineup would be an avidly sought collector’s item today:

Os Oito Batutas in 1923. Pixinguinha stands on the extreme right.

Pixinguinha—Alfredo da Rocha Vianna Jr. (1897–1973). Brazil’s greatest choro composer and flutist, pioneering arranger and tenor saxophonist. Author of such classics as “Carinhoso”; “Rosa”; “Ingênuo”; “Naquele Tempo”; “Página de Dor”; “1 x 0”; “Lamentos”; “Cochichando”; and “Vou Vivendo,” among many others. Founder of the legendary ensemble Os Oito Batutas (1919), as well as of Diabos do Céu, Guarda Velha (1932), and Velha Guarda (1954), he was a pioneering arranger of popular music in countless recordings. In the Stokowski recordings, Pixinguinha played his brilliant flute on various tracks, as well as singing a duet with Jararaca.

Courtesy of the Agenda do Samba & Choro

Donga—Ernesto Joaquim Maria dos Santos (1891–1974). Guitarist and son of Tia Amélia, one of the celebrated baianas of Praça Onze. In 1916, Donga began to play with Pixinguinha at Tia Ciata’s house, where he co-authored “Pelo Telefone,” the first recorded samba and the carnaval hit of 1917. Composer of “Patrão, Prenda Seu Gado” (with Pixinguinha & João da Bahiana); “Quando uma Estrela Sorri” (with Villa-Lobos & David Nasser); “Benedito no Choro”; and “Seu Mané Luiz” (with Baiano). Co-founder of Os Oito Batutas, Guarda Velha, and Velha Guarda. Donga’s conjunto regional provided much of the accompaniment in the Stokowski recordings.

João da Bahiana—João Machado Guedes (1887–1974). Son of another influential baiana, Tia Prisciliana (or Perciliana). He began parading in Carnaval groups while still a boy of ten and was a member of the legendary ranchos Kananga do Japão and Deixa Falar. For many years the most important percussionist in Brazil, he is credited with having introduced the pandeiro into samba and choro and turned the knife and plate into a rhythm instrument. Composer of the sambas “Batuque na Cozinha” (resurrected by Martinho da Vila); “Mulher Cruel”; “Pedindo Vingança”; and “O Futuro É uma Caveira.” Noted singer of Afro-Brazilian corimas. A lifelong friend of Pixinguinha and Donga and co-founder of Guarda Velha and Velha Guarda.

Cartola—Angenor de Oliveira (1908–1980). Co-founder of the samba school Estação Primeira de Mangueira and one of the most outstanding samba composers and performers of all time. Author of the immortal “As Rosas Não Falam”; “Acontece”; “Alvorada”; “O Sol Nascerá”; “Sim”; “O Mundo É um Moinho”; “Disfarça e Chora”; “Os Tempos Idos”; “Ao Amanhecer”; “Tive Sim”; and “Cordas de Aço,” to name a few. At the Stokowski sessions, where he made his first vocal recordings, Cartola was accompanied by Mangueira composer/guitarist Aluísio Dias; a group of Mangueira percussionists including Preguiça, China, and Negro; and the samba school’s pastoras, a feminine chorus made up of Neuma, Cecéia, Nadir, Ornélia, Guiomar, Nesilia, and Neguinha.

Zé Espinguela—José Gomes da Costa (1901–1944). Pai-de-santo and important samba pioneer. When samba was still illegal, Espinguela hosted rodas de samba at his house following the macumba ceremonies. Headed the Bloco dos Arengueiros in the morro of Mangueira (first Carnaval parade: 1927), from which emerged the seven founders of the samba school Estação Primeira de Mangueira, Espinguela among them. Invented the samba school competition in 1929. In 1940, assisted Villa-Lobos in the creation of the old-style carnaval group Sodade do Cordão. Popularly known as Pai Alufá, he was accompanied in the Stokowski recordings by the vocal-instrumental-dance group that usually performed at his parties, be they sacred or profane. These were the only vocal recordings made by Espinguela, also known as José or Zé Spinelli.

Zé da Zilda—José Gonçalves (1908–1954). Mangueira composer first known as Zé com Fome (Hungry Zé) for his habit of stashing enormous quantities of food from friends’ parties in his guitar case. Later he formed a duo with wife Zilda and received the new nickname. Co-author with Cartola and Carlos Cachaça of “Não Quero Mais [Amar a Ninguém]” and with Marino Pinto of Orlando Silva’s hit “Aos Pés da Cruz.”

Jararaca and Ratinho—Famous northeastern comic duo of composer-actors. José Luis Rodrigues Calazans “Jararaca” (1896–1977) and saxophonist Severino Rangel de Carvalho “Ratinho” (1896–1972) spread their humorous cocos and emboladas all over Brazil by means of their wildly popular radio program. Jararaca’s 1936 marcha “Mamãe Eu Quero” is one of the most popular carnaval tunes of all times.

Luiz Americano—Notable choro composer (1900–1961) and important clarinetist and saxophonist. Composed and recorded the choro “É do que Há!” in 1931. In 1938, he composed “O Pandeiro do João da Bahiana.” In 1953, he would record Ratinho’s choro “Saxofone, por que choras?” The following year, Ary Barroso would cite him as one of the most important popular musicians in Brazil.

Janir Martins (courtesy Barão do Pandeiro)Also participating were singer Janir Martins of the Rádio Nacional (the only female soloist), Donga’s conjunto regional featuring singer Mauro César (real name: José Nascimento), and the men’s chorus of Orfeão Villa-Lobos. In his biography of Pixinguinha, Sérgio Cabral mentions additional illustrious names associated with the recording session: Paulo da Portela (founder of the Portela samba school), Augusto Calheiros, and guitarist Laurindo de Almeida. Two other legendary sambistas, Ataulfo Alves and Carlos Cachaça, were invited but didn’t show up (Carlos Cachaça, a lifelong employee of the Federal Railways who never missed a day’s work, had to be at the Central do Brasil train station that night).

The S.S. Uruguay docked at Praça Mauá in Rio de Janeiro. It was one of three Good Neighbor ships owned by American Republics Line and operated by Moore-McCormack Lines. In May 1939, the Uruguay brought Carmen Miranda to New York for the first time. (photo courtesy of Leon van Duivendijk)Where were the recordings made?

Columbia had a recording studio in Rio de Janeiro, and that would have been the natural place to hold the sessions. But the Columbia affiliate in Brazil, Byington & Cia., wasn’t even notified. Instead, the musicians came aboard the S.S. Uruguay, where the great salon was outfitted with recording equipment courtesy of Columbia. Present during the recordings were not only the artists, but members of the press, musicians of the AAYO, ship passengers, and even the captain.In his book Todo Tempo que Eu Viver (Rio de Janeiro, Corisco Edições, 1988), the filmmaker Roberto Moura quoted a reportage published in the newspaper A Noite on 8 August 1940:

[...] In its entire existence, the music salon of the Uruguay had perhaps never held so many celebrities as it did last night. [...]

At 10 pm began the gathering of conjuntos, escolas de samba, orchestra, people who were going to sing and people who were going to listen. In this last group was the ship’s captain himself, who soon took a place in a commodious armchair, from where he observed the whole parade.

Pixinguinha, Jararaca, Ratinho, Luís Americano, Augusto Calheiros, Donga, Zé Espinguela, Mauro César, João da Baiana, Janir Martins, a wing of Saudade do Cordão [sic], that garnered so much success in the last carnaval, the Escola de Samba Estação Primeira de Mangueira, the songwriter David Nasser, all these people talk, comment, discuss, until the recording work begins. As the hands of the clock move forward, the passengers of the Uruguay return from their tours in the city and take their places in the vast salon. And the groups who are recording follow each other in front of the microphone.

Midnight was long past when the maestros Stokowski and Villa-Lobos arrived. The photographers bestir themselves, eager to catch them in unexpected moments, but the famous conductor from Philadelphia flees discreetly from their lenses. Finaly he disappears altogether. But in his place remains Pixinguinha, who commands the general attention with his famous “Urubu Malandro”.

From one number to the next, the night passes and dawn surges. The music salon of the Uruguay is still full. Now the audience consists mainly of members of the All American Youth Orchestra, who are curious to learn about the Brazilian instruments. By morning, the sound engineer is able to count more than a hundred recordings. That is the work of one night, and also Brazilian music in its most typical expression, which will go to other countries of the Continent to serve the policy of pan-American approximation of the peoples in this hemisphere.

In short, the night was as much a social gathering as a working session, and recording conditions in the crowded salon were far from ideal, as can be easily ascertained from the albums Columbia released. The sound engineer was American—quite unfamiliar with Afro-Brazilian music and instruments—and he had to contend with recording at least forty numbers in one session. This was only the first intimation that Brazil’s “Good Neighbor” wasn’t assigning much importance to the music.

On Thursday, 8 August 1940, the newspaper O Globo announced on page one:

Samba, Stokowski’s attraction!

During eight consecutive hours, the famous conductor recorded close to 40 Brazilian popular tunes.The previous evening, after his concert at the Teatro Municipal, Stokowski had returned to the ship to oversee the recordings. He retired exhausted at 3 am, but the recordings continued until daylight. According to some accounts, the session was resumed on the following night, but no information is available as to what might have been recorded then.

What was recorded on the night of 7 August and the morning of the 8th?

At least two detailed accounts exist, drawing on newspaper reports of the period. The accounts don’t match perfectly.In his biography Pixinguinha, Vida e Obra, Sérgio Cabral quotes O Globo:

First, the maracatus and the frevos composed by Pixinguinha. Then choro solos by Luiz Americano and his conjunto. The sung portion began with Janir Martins, a Rádio Nacional singer possessing a good voice and good samba interpretation, and José Gonçalves, in Seu Mané Luiz. The same José Gonçalves recorded the samba de breque Uma Festa de Zés. The Estação Primeira de Mangueira, samba school, then sang four Cartola productions, all of the most legitimate flavor of our morros. Jararaca and Ratinho performed a desafio at the microphone and interpreted the difficult embolada Bambo no Bambu. To follow, Augusto Calheiros relived the modinhas of Catulo da Paixão Cearense. Into the scene entered the veterans of Sodade do Cordão [an attempt by Villa-Lobos to resurrect, in 1940, ancient carnaval manifestations] in an impressive presentation of monotonous melodies, at times noisy, others of the black magic. After four such recordings, two marchas de rancho by Donga and Davi Nasser were committed to wax: Meu Jardim and Quando uma Estrela Sorri, recorded by the Estação Primeira de Mangueira with soloist Mauro César. Composed by the same authors, the sambas Samba da Lua and Sofre Quem Faz Sofrer were recorded by Janir Martins & José Gonçalves and by Mauro César, respectively. Then came the number that caused the greatest sensation of the night: the flute solo of Pixinguinha in Urubu Malandro. All present were enthusiastic, not only with the picturesque music but with the superb execution of Pixinguinha, to the point that one of the orchestra’s section leaders said, “That is one of the best flutists I’ve ever heard.”The researchers Marília Trindade Barboza and Arthur L. de Oliveira pieced together newspaper reports replete with inaccuracies, omissions, and duplications to produce the following list of tunes, published in two of their biographies, Filho de Ogum Bexiguento (about Pixinguinha) and Cartola—Os Tempos Idos:

01. Seu Mané Luiz (partido alto by Donga & Cícero de Almeida)

02. Meu Amor (samba do morro by Cartola & Aluísio Dias)

03. Festa Encrencada (samba de breque by José Gonçalves)

04. Passarinho Bateu Asas (toada by Donga)

05. Sapo Dentro do Saco (embolada by Jararaca)

06. Orimé (macumba by Zé Espinguela)

07. Hoje É Dia (macumba by Zé Espinguela)

08. Afoché (candomblé by Zé Espinguela)

09. Samba da Lua (batucada by Donga & David Nasser)

10. Intrigas no Buteco do Padilha (choro by Luiz Americano)

11. Tocando pra Você (choro by Luiz Americano)

12. Luiz Americano no Lido (choro by Luiz Americano)

13. Bole-Bole (maxixe by José Gonçalves)

14. Caboclo do Mato (fantasia on macumba by João da Bahiana)

15. Quequerequequê (fantasia on macumba by João da Bahiana)

16. Pelo Telefone (samba by Donga & Mauro de Almeida)

17. Bambu (embolada by Donga)

18. Primeiro Amor (samba do morro by Cartola & Aluísio Dias)

19. Apanhá Limão (samba by Jararaca)

20. José Barbino (maracatu by Pixinguinha & Jararaca

21. Na Praia (modinha by Raul Moraes)

22. Saia da Morena (embolada by Donga)

23. Tristeza (samba do morro by Cartola)

24. Quem Me Vê Sorrir (samba do morro by Cartola & Carlos Cachaça)

25. Ranchinho Desfeito (samba-canção by Donga & David Nasser)

26. Cambinda Velha (frevo by Pixinguinha)

27. Urubu Malandro (variations on samba by Pixinguinha)

28. Amarra a Vaca (embolada by Jararaca)

29. Alma de Tupi (modinha by Jararaca)

30. Taco Taco (desafio by Jararaca)

31. Sofre Quem Faz Sofrer (samba by Donga & David Nasser)

32. Romance de um Índio (samba by Donga & David Nasser)

33. Curimachô (macumba by Zé Espinguela)

34. Camandauê (candomblé by Zé Espinguela)

35. Meu Jardim (marcha de rancho by Donga & David Nasser)

36. Ranchinho Desfeito (marcha de rancho by Donga & David Nasser)

37. Acoroagô (candomblé by Zé Espinguela)

38. Canide-Ione (Amerindian chant elaborated by Villa-Lobos)

39. Nozani-Na (Amerindian chant elaborated by Villa-Lobos)

40. Teiru (Amerindian chant elaborated by Villa-Lobos)“Ranchinho Desfeito” is listed twice, the second time as a marcha de rancho. According to Barboza and Oliveira, the song was recorded twice, but it could be that this marcha de rancho is “Quando uma Estrela Sorri” (by the same authors), mentioned in the O Globo report but missing from the list above.

On Friday, 9 August, with at least forty tunes recorded (some say a hundred), Stokowski bid adieu to Rio de Janeiro and left for São Paulo. What did he give the musicians for their work? Only his enthusiastic compliments.

Scans: Jim BraunII. Scherzo poco allegro: Native Brazilian Music

Columbia Records released Stokowski’s Uruguay recordings in early 1942 (see the review published in Time magazine) under the title Native Brazilian Music. Of the forty tunes recorded, only seventeen saw the light of day, in two albums, each containing four 78-rpm discs. The albums’ liner notes announced:

Here in this album of Columbia Records you have the authentic music of Brazil...superbly played by native musicians...selected and recorded under the personal supervision of Leopold Stokowski.

These significant recordings were made during Maestro Stokowski’s tour of South America with the All-American Orchestra. At the various stops of the tour, Dr. Stokowski listened to the native folk and popular music as interpreted by the musicians of our Good Neighbor states. For recording purposes he chose what he thought was best and most typical.

Plans for these records were laid when arrangements were first completed to record, exclusively on Columbia Masterworks, the All-American Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski.

Pixinguinha’s acclaimed flute solo in “Urubu Malandro” was one of the many casualties. But truncation wasn’t the only deficiency of the albums. A mere six of the seventeen tune titles escaped butchery on the disc labels. Of the composers’ names, a scant three were correctly spelled. As for the performers, they were mostly ignored. In Volume Two, the song order was mixed up. And considering Stokowski’s zeal for “the most legitimate native Brazilian music,” the descriptions attached to the compositions are disappointingly inadequate. I’ve reformatted the label information for easier reading, although the spelling and the order remain as they were on Columbia’s discs:

Scan: Jim BraunNative Brazilian Music, Vol. One, Set C-83

36503 C83-1 (CO 30165) Grupa do Rae Alufá: Macumba de Ochócê (Jose Espingucla); Macumba with Vocal Ensemble

36503 C83-2 (CO 30166) Grupo do Rae Alufá: Macumba de Inhançan (Jose Espingucla); Macumba with Vocal Ensemble

36504 C83-3 (CO 30150) Regionale Orchestra: Samba Concao (Wasson-Donga); Samba with Vocal Refrain

36504 C83-4 (CO 30151) Regionale Orchestra: Caboclo do Matto (Cetulio Marinho); Samba with Vocal Ensemble

36505 C83-5 (CO 30154) Guarda Vilha Orchestra: Seu Mané e Luiz (Ernesto dos Santos); Samba with Vocal Duet

36505 C83-6 (CO 30156) Ernesto dos Santos with Orchestra: Bambo du Bambu; Samba with Vocal Refrain

36506 C83-7 (CO 30155) Jararaça e Rattinho: Sappo no Sacco (Jararaça e Rattinho); Embolada with Ensemble Vocal

36506 C83-8 (CO 30147) Regionale Orchestra: K Keri K K (Yoad Machrado Cudo j); Samba with Vocal Ensemble

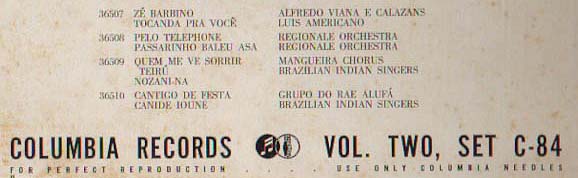

Scan: Jim BraunNative Brazilian Music, Vol. Two, Set C-84

36507 C84-1 (CO 30152) Alfredo Vianna e Calazans: Zé Barbino (Alfredo viana e Calazans); Vocal

36507 C84-2 (CO 30153) Luis Americano: Tocanda Pra Voce (Luis Americano); Instrumental

36508 C84-3 (CO 30148) Regionale Orchestra: Pelo Telefone (Donga); Zamba with Vocal Chorus

36508 C84-4 (CO 30149) Regionale Orchestra: Passarinho Baleu Asa (Donga); Zamba with Vocal Ensemble

36509 C84-5 (CO 30163) Mangueira Chorus: Quem Me Ve Sorrir (de Oliveira); Zamba with Vocal Ensemble

36509 C84-6 (CO 30193) Brazilian Indian Singers: 1. Teirú 2. Nozani-Na (Villa-Lobos); Chants

36510 C84-7 (CO 30190) Grupo do Rae Alufá: Cantigo de Festa (Jose Espingucla); Canção with Vocal Ensemble

36510 C84-8 (CO 30167) Brazilian Indian Singers: Canide Ioune (Villa-Lobos); VocalColumbia never released Native Brazilian Music in Brazil, and for forty-seven years, the only known copies there could be counted on the fingers of one hand. The music historian and critic Lúcio Rangel was one of the lucky few who owned the albums—he received them from a friend in New York into whose hands they had fallen by chance. Rangel eventually donated his albums to the Museu da Imagem e do Som (MIS), where they disappeared in mysterious circumstances.

Zé Espinguela & Villa-Lobos (right) during a Sôdade do

Cordão rehearsal at Espinguela’s house, 1940 (photo courtesy

of Ermelinda A. Paz).Most of the musicians died without ever having heard the recordings. Few were paid for them. Cartola received a paltry 1,500 réis, enough for three packets of cheap cigarettes, a year and a half after the recordings. In an interview he gave Sérgio Cabral in 1974, Cartola said that he finally heard “Quem Me Vê Sorrir”—his first vocal recording—in Lúcio Rangel’s home a good twenty years after the Uruguay sessions. Two other participants in the same recording, Aluísio Dias (1911–1991) and Dona Neuma Gonçalves Silva, had to wait until 1980 to hear it on tape. Dona Neuma (1922–2000) was the daughter of Mangueira’s first president Saturnino Gonçalves and the grande dame of samba. In 1940 she was eighteen and one of the pastoras who provided the electrifying vocal backup in “Quem Me Vê Sorrir.” In a 1981 interview with filmmaker Roberto Moura, Dona Neuma still remembered fondly and described in great detail the delicious food served on board the Uruguay 41 years earlier:

Like me, the elders who came... I was still a kid, but the elders who came, came to eat, there were lots of good things for us to eat, that was the first time that we ate turkey with pineapple, pork with prunes, a luxurious supper. We recorded, after the party there was the reception. [...] It happened all on the same day. It was fast. It was in the evening, but the samba went on until morning. I slept on deck, how nice it was. [...] There was a type of vermicelli with ham, cheese, I don’t know, it wasn’t spaghetti but vermicelli, very well prepared, loose, it wasn’t the sticky mess we get when we cook vermicelli, this was very well done, I don’t know how they cooked it, but it turned out loose, I think they made the sauce and then cooked the pasta in it, they gave it a little twist that kept it loose, a delicious thing, but I only wanted to eat, you know? Eat and walk [around the ship]. [...]

It was a beautiful ship. [...] A beautiful salon, there was a stage, we sang on the stage, with him conducting. He conducted us, there was an orchestra and our drums. [...] He conducted the orchestra, then he came and conducted us and the drums. We already knew because maestro Villa-Lobos taught us the hand gestures, how it went, if he raised it, we knew all the gestures, taught by maestro Villa-Lobos. He taught here, at the school, everywhere, because the maestro that we knew at that time was Villa-Lobos, it was he. He came here to the morro a lot, because he was a great friend of Cartola.

Neither the government of Brazil nor any other Brazilian entity has ever made an effort to recover these recordings. In 1987, during Villa-Lobos’ centennial, Museu Villa-Lobos (MVL) in Rio de Janeiro released the sixteen Native Brazilian Music sides on an LP produced by Suetônio Valença, Marcelo Rodolfo, and Jairo Severiano, with liner notes by the music historian Ary Vasconcelos. The music was transferred not from the original matrices, whose location (if they survived) remained unknown, but from 78-rpm discs donated by the collector Flávio Silva.

This also was the first time that the compositions, their authors, and the interpreters were correctly identified, the exception being Pai Alufá (Zé Espinguela), whose group inexplicably retained the moniker Grupo do Rae Alufá, à la Columbia (I corrected the name below):

Native Brazilian Music, Vol. 1 (C-83)

1. Macumba de Oxóssi (Donga/José Espinguela)

Zé Espinguela & Grupo do Pai Alufá

A macumba in praise of Oxóssi, orixá of the forest and the hunt, syncretized as St. Sebastian in Rio de Janeiro and as St. George in Bahia. Short call & response phrases in Yoruba, sung by a male soloist and a female chorus and accompanied by powerful drumming (titled “Orimé” [#6] in the list of 40 tunes).2. Macumba de Iansã (Donga/José Espinguela)

Zé Espinguela & Grupo do Pai Alufá

A macumba in praise of Iansã, female orixá of the flaming sword, syncretized as St. Barbara. Male soloist and female chorus accompanied by drumming (titled “Camandauê” [#34] in the list of 40 tunes).3. Ranchinho Desfeito (Donga/De Castro e Souza/David Nasser)

Mauro César

A simple Samba-canção, sung in Orlando Silva’s vocal style and accompanied by Donga’s conjunto regional and Pixinguinha's outstanding flute (#25 in the list of 40 tunes).4. Caboclo do Mato (Getúlio Marinho da Silva “Amor”)

João da Bahiana, Janir Martins & Jararaca

Corima featuring short phrases of call (João) and response (Janir & Jararaca), flute improvisations by Pixinguinha, and João’s famous pandeiro (#14 in the list of 40 tunes).5. Seu Mané Luiz (Donga)

José Gonçalves (aka Zé da Zilda) & Janir Martins

Humorous samba in a male-female duet, accompanied by Donga’s regional with Pixinguinha's flute solo and percussion (#1 in the list of 40 tunes).6. Bambo do Bambu (Donga)

Jararaca & Ratinho

Typically fast-paced, tongue-twisting embolada, accompanied by a regional with Laurindo de Almeida’s guitar. (#17 in the list of 40 tunes).7. Sapo no Saco (Jararaca)

Jararaca & Ratinho

A classic rapid-fire embolada, sung in duet and accompanied by a regional, this was one of the few previously recorded (in 1929) tunes included in the Columbia albums (#5 in the list of 40 tunes).8. Que Quere Que Quê (João da Bahiana/Donga/ Pixinguinha)

João da Bahiana & Janir Martins

Macumba carnavalesca featuring male call & female response, with João’s pandeiro and Pixinguinha's flute improvisations. Previously recorded in 1932 as "Que Querê" with authorship attributed to the three musicians, it was probably composed by João alone (#15 in the list of 40 tunes).

Photo: Daniella ThompsonNative Brazilian Music, Vol. 2 (C-84)

1. Zé Barbino (Pixinguinha/Jararaca)

Pixinguinha & Jararaca

A maracatu featuring brass & percussion instrumentals interspersed with male-duo vocals. A rare vocal recording by Pixinguinha (#20 in the list of 40 tunes).2. Tocando pra Você (Luiz Americano)

Luiz Americano

A choro in three parts [structure: a-b-a-c-a] with clarinet solo accompanied by a regional, with João da Bahiana on pandeiro (#11 in the list of 40 tunes).3. Passarinho Bateu Asas (Donga)

José Gonçalves (aka Zé da Zilda)

Samba with male solo & male-female refrain, accompanied by Pixinguinha’s flute and Donga’s regional. This famous composition had been recorded by Francisco Alves in 1928 (#4 in the list of 40 tunes).4. Pelo Telefone (Donga/Mauro de Almeida)

5. Quem Me Vê Sorrir (Cartola/Carlos Cachaça)

José Gonçalves (aka Zé da Zilda)

The celebrated samba, with male solo & female chorus, Pixinguinha’s brilliant flute, and Donga’s regional (#16 in the list of 40 tunes).

Cartola & Mangueira’s Chorus

Another classic samba sung by Cartola and Mangueira’s high-voiced pastoras, with expressive cuíca grunts, Aluísio Dias on guitar, and powerful drumming by Mangueira percussionists (#24 in the list of 40 tunes).6. Teiru/Nozani-Ná (Traditional/Heitor Villa-Lobos)

Choral Quartet of Orfeão Villa-Lobos

Two Amerindian chants, slowly and deliberately intoned by four teachers of the Orfeão Villa-Lobos. “Teiru” is a funeral chant for the death of a chief, collected by Roquete Pinto in 1912. In 1926, Villa-Lobos made it the second of his Três Poemas Indígenas. “Nozani-Ná” is included in Villa-Lobos’ Canções Típicas Brasileiras (1919). (#39 & #40 in the list of 40 tunes).7. Cantiga de Festa (Donga/José Espinguela)

Zé Espinguela & Grupo do Pai Alufá

Corima featuring male solo & female chorus, drumming, and clapping (#7 in the list of 40 tunes).8. Canidé Ioune (Traditional/Heitor Villa-Lobos)

Choral Quartet of Orfeão Villa-Lobos

This Amerindian chant, collected by the traveler Jean de Léry in 1553, is the first of Villa-Lobos’ Três Poemas Indígenas, published in 1926. It is sung by the teachers of the Orfeão Villa-Lobos. (#38 in the list of 40 tunes).III. Andante vivace: California, 1999

I first heard about Native Brazilian Music from Paulo “Pauleira” Malaguti. In April 1999 I was interviewing him for an article about his vocal group, Arranco de Varsóvia (Brazzil, May 1999). Arranco had recorded Cartola & Carlos Cachaça’s samba “Quem Me Vê Sorrir”—now better known as “Quem Me Vê Sorrindo”—on their CDs Quem É de Sambar and Samba de Cartola, and Malaguti described his first encounter with the song:

In 1993 I was given one of these [MVL] records that were released here and was very impressed with the whole album and particularly with this specific track. The blending of a very delicate melody and poem, the sound of the pastoras with the early Mangueira drumming, made a deep impression on my understanding of the history of samba. So I used exactly the same form as the original recording, making my own polyphony for the intro and harmonizing the main melody. This melody is so well done that it makes it easy for the arranger to create the other voices to accompany it. This song remains for us at Arranco a very powerful greeting card when we make short appearances. This is the song that we first showed Beth Carvalho, and she was sincerely touched by our singing. We recorded it again on our second album in a slightly different version.

In early May, I acquired the newly released CD Cartola—O Sol Nascerá (Revivendo RVCD-131), which contains Cartola compositions recorded between 1929 and 1968, including the rendition of “Quem Me Vê Sorrir” from the Stokowski sessions. The contrast between Cartola’s delicate singing and the pastoras’ strongly African–tinged accompaniment was captivating, and my curiosity, always active, was powerfully piqued. At this stage, all I knew about the Stokowski recordings was that they were made in 1940 on board the Uruguay, and that Villa-Lobos rounded up Cartola and the “Mangueira crowd,” Donga, Jararaca & Ratinho, Luiz Americano, Zé Espinguela, and others to record “many different things” (in Malaguti’s words).

Later that month I flew to Rio de Janeiro, where the collector Valfredo Guida let me hear the entire MVL album and gave me a tape dub with a hand-written track list that specified titles and composers but not performers. I treasure the tape, but the whole matter might have rested right there were it not for another friend’s action.

Toward the end of July 1999, I received an e-mail from Jim Braun, who programs and presents music shows on KBOO radio in Portland, Oregon. Jim wrote that he was sending me a tape dub of “a 78-rpm Columbia album called Native Brazilian Music—Volume 1 (I think there never was a Volume 2), which has some stuff I’m sure you’ll find interesting.” As a footnote, Jim added, “Re the Native Brazilian Music album: on every side’s label it says ‘Recorded under the personal supervision of LEOPOLD STOKOWSKI.’ I don’t believe it, but I suppose they thought it would help in the marketing.” I told Jim to believe it and sent him what little information I had. He replied, “Thanks a million for the Stokowski info; it couldn’t have been more timely, since I’m planning to air all eight sides on my next show this Friday—from cassette tape, of course, since KBOO doesn’t have a 78-rpm turntable.” Few of the titles of Jim’s eight recordings matched the list I got with my Rio tape, and it was only after I’d read further and listened to Jim’s tape that I realized the recordings were identical.

Just that week, I was reading Pixinguinha’s biography Filho de Ogum Bexiguento, freshly acquired in a Rio sebo. And there, on page 102, was laid out the story of the Stokowski sessions, including a list of forty tunes recorded on board the Uruguay.

Forty tunes, when only seventeen had been released on sixteen sides.

Now genuinely excited, I seized Cabral’s Pixinguinha, Vida e Obra, then his As Escolas de Samba do Rio de Janeiro, and learned much of what you’ve read thus far. Painstakingly, I pieced together information from disparate sources to identify the seventeen Native Brazilian Music tunes, their composers and performers.

It dawned on me that somewhere, perhaps in the Columbia vaults in this country, there might be languishing 23 never-released recordings made by some of Brazil’s greatest musicians. Did anyone know about them or have a clue as to their whereabouts?

By sheer coincidence, I was just completing an article about the samba group Família Roitman (Brazzil, July 1999). The group’s guitarist, Felipe Trotta, told me he was working at Museu Villa-Lobos on a temporary basis, and I sent him a series of questions that he forwarded to Marcelo Rodolfo, the museum staffer involved in the release of NBM.

Daniella Thompson—Has MVL ever released these recordings on CD? If so, is it available for purchase?

Marcelo Rodolfo—Unfortunately not yet.

DT—What ever happened to the other 23 recordings made for Stokowski on board the ship Uruguay on 7 and 8 August 1940? Columbia never released them.

MR—We have no idea.

DT—Were the masters ever returned to Brazil? Do they still exist?MR—We also don’t know. Museu Villa-Lobos issued in 1987 an LP version directly from those known 78-rpm albums.

Sorry if we couldn’t help you much, but we think you can get more information about the recordings from Suetônio Valença. He is an expert in Brazilian music and was one of those responsible for that release.

We hope you get success in your investigation.[In 2001, a Brazilian reader told me that he had asked Marcelo Rodolfo why he hadn’t made more of an effort to help me in the investigation. Rodolfo replied, “She was too eager.”]

It was time to launch an all-out attack. I sent an e-mail to Paulo Malaguti and asked him to contact Suetônio Valença. I also posted a query to the Brazilian music e-mail list Saudades do Brasil, asking if anyone knew how one might go about looking for old recording masters in Sony’s Columbia vaults. The only immediate response came from Jack O’Neil, owner of Blue Jackel Entertainment—an American label that has released a significant amount of quality Brazilian music. Jack wrote:

Sony Brasil is very well organized and can find just about anything you ask for. Sony/Columbia US is the complete opposite. If it is older than 10 years, they cannot find anything.The next day he added:

You should forget about dealing with Sony USA; they will have no records about this release. You should deal with Sony Brasil; maybe they can make a copy for you on DAT or CD. Sony Brasil was the only label that still knew what they had in 78s when we were licensing. It sounds like a great disc.Jack’s news was not what I’d hoped to hear, but buoyed by his interest, I told him the whole tale. He replied, “What a great story. This is what makes the world go around,” and advised that there’s a reliable way to transfer music from 78s to CD, concluding:

If they were never released in Brasil, then you have to find someone in the US that will track them down. Sony Special Products are a licensing division, but if you tell them you are interested in licensing, maybe they will dig around for you. It’s a process that usually takes about 6 months.Again, Jack’s information was both encouraging and discouraging. There might be a way to locate the original masters, but becoming a producer was the last thing I wanted to do. In the meantime, I heard from Malaguti:

I talked to Suetônio right this moment, and he is very willing to help you. I think he possesses the original Columbia records, and he says that the masters must be at Columbia up to this point. I couldn’t get into much detail on what your interest is, but he was curious and gave me his e-mail for you to get in contact. You should rush because he will be out of town tomorrow on a trip to Prague for some radio programs he made.So I wrote Suetônio Valença a long e-mail, suggesting that perhaps a label like the Brazilian Revivendo, which specializes in reissuing historic recordings on CD, might be interested in releasing NBM. Somewhere along the way, my interest had shifted from the mere desire to hear all forty recordings to the conviction that this treasure should be unearthed and released on disc. But could it be recovered? And would I have to turn myself into a producer to do it?

I was pondering the imponderable when a few days later another reply to my listserv query arrived. This time it was my friend Luca DiDonna, an audiophile collector of Brazilian music. Luca told me that a recent issue of the audiophile magazine Absolute Sound contained an article about Columbia Records during the ’50s, written by Michael Gray of the Library of Congress. An unhoped-for ray of light. I sent an e-mail to Sony’s Columbia division. Needless to say, that message has yet to be answered. Next I searched for the Absolute Sound website and dispatched an e-mail to its publisher, Mark Fisher, who forwarded my message to Michael Gray. Gray soon got in touch, and I recounted the long tale again. His response:

I was aware that LS had made records with the AAYO in Brazil, but not about the discs of Brazilian music.

I have many friends at Sony—perhaps you could send me a list of matrix numbers and I can see if the masters survived. Is that OK?

Obrigado (I think!)Another mad scramble. An e-mail to Jim Braun, with instructions for locating the matrix numbers on the eight sides of his NBM, Vol.1. A ninth matrix number came from a photo of one of the Vol. 2 discs, reproduced in Cabral’s Pixinguinha (the disc label still bore the legend ‘Volume One’, although the side was identified as C84-1—Side 1 of Volume Two). More e-mails to researchers in Rio de Janeiro yielded no helpful information. But those nine numbers were sufficient, and I didn't have to wait long. Twelve days later, there was an e-mail from Mike Gray:

Do you have a FAX number? I found some material at the Library of Congress today that might be useful, though somewhat disappointing if you’re looking for those missing masters...The fax arrived the following day, comprising several pages of microfiche, listing recordings from 1941 and ’42. There—sandwiched between Eddy Duchin’s “Sometimes” & “How About You” and Orrin Tucker’s “Goodbye Mama” & “You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap” on one side and Kate Smith’s “America, I Love You” & “The Star-Spangled Banner” on the other—were my sixteen NBM sides, botched spelling and all, although not necessarily the same misspellings as on the Columbia discs. “Passarinho Bateu Asas” (A Bird Beat Its Wings), which turned into “Passarinho Baleu Asa” on the disc label, had become “Passarinho Bazeu Aza” in the Library of Congress archive. A few tunes recovered their legitimate titles. Recording place: unknown. Recording date: 12 March 1941. In the margin of the fax, Mike Gray added:

I also looked at the daily engineering and dubbing reports for 1940/41, but I can’t find the original master numbers or the dubbing dates that made the COs. Given your own recording information, the 3/12/41 date probably means a date received rather than a recording date. Hope all this helps a little...What Mike Gray was telling me ever so gently was that he believed the masters hadn’t been preserved—the final insult in a long inventory of injuries.

The next day I heard from the music collector, researcher, and producer Paulo Cesar de Andrade:

Unfortunately I couldn’t get the matrix numbers of the recordings. In Brazil, we use recording numbers, not matrix numbers, in discographies. If the recordings made in Brazil are 40 and you can get them, we can produce a box of 2 CDs with the complete historical recordings. I'm crossing my fingers.My own fingers were no longer crossed. Scratch Plan A. I sent out a flurry of e-mails to let people know that the NBM masters probably haven’t survived. Jack O’Neil replied:

This is what I mean; so much great old stuff is gone. The 78s can serve as a master in the right hands. To release or license a full CD from a major label is very difficult. They want to manufacture it and ship you finished product for a ridiculous sum of money. I would love to hear this stuff. Maybe if I fall in love with it [I could] help out.My tape recorder possesses only a single recording head, so once again I turned to Jim Braun. He asked an astute question to which I could furnish no answer: “Could the masters be resting in Columbia's vaults unbeknownst to the L of C?” and willingly agreed to send Jack a tape of the eight sides in his NBM, Vol. 1. Thinking ahead, he added:

Meanwhile, I’ve been thinking: if the two-CD set is impossible, how about a single CD containing the sixteen sides issued by Columbia? Surely a decent copy of NBM, Vol. 2 must be obtainable somewhere. I’ve looked at rec.music.marketplace.misc with an eye to advertising there, and I’ve also come across a mailing list for 78 collectors. What do you think?

Photo: Daniella ThompsonIV. Coda

Jim Braun sent the promised tape to Jack O’Neil. Jack liked the material and even said that he’d love to release it, but he thought it would be impossible to license the rights from Sony, since no one there knows that the material exists. The owner of Rob Digital, a Brazilian record label focusing on choro, reacted in a similar manner. As for Jim, in September 1999 he found Vol. 2 of NBM offered for sale on the Internet and bought it (he had acquired his first volume in some garage sale or thrift shop). Suetônio Valença eventually wrote back but had no new information to offer beyond saying that MVL should reissue NBM on CD (“should” is not the same as “will”). He promised to send me the liner notes for the MVL 1987 LP edition but never got around to doing so. I was presented with a copy of the MVL LP in March 2000 and incorporated the final details into the article as it was going to press. My overtures to Revivendo have yet to bear fruit. Jim Braun recently told me that he’s ready to make his 78-rpm discs available should any label be willing to release NBM on CD.

We’re still waiting.

= = =

There’s an aftermath to this story.

Glossary

Batucada: Afro-Brazilian song & dance performed since the 17th century and consisting of sung verses (with choral response) accompanied de percussion instruments. Since the 1930s, the term signifies a specific type of samba with strong percussive accompaniment.

Batuque: the rhythm of batucada.

Batuqueiro: competitor or player in a roda de batucada.

Candomblé: Afro-Brazilian religion synthesized in Bahia by slaves from Angola, Congo, Efan, and principally from Yoruba- and Fon/Ewe-speaking regions (now Nigeria and Benin); also the music performed during candomblé rites.

Choro: instrumental music of 19th-century origin, noted for virtuosity, improvisation, and counterpoint.

Coco: popular northeastern song and dance form whose verses are sung in call-and-response fashion by a soloist and chorus, accompanied by percussion and clapping.

Conjunto regional: traditional instrumental ensemble, playing samba or choro.

Coqueiro: coco lead singer, also known as tirador de coco (coco puller).

Cordão: cordon, a carnaval group of old times, utilizing Indo-Brazilian themes and primitive percussion.

Cordão de velhos: cordon of old-timers.

Corima: Afro-Brazilian genre related to jongo, featuring soloist and chorus call-and-response singing, dancing, and drum accompaniment. Its variants assume the names of the specific drums used (e.g., caxambu).

Desafio: challenge; poetic dispute between two singers, partly improvised and partly set; practiced all over Brazil, but especially in the northeast. Musical instruments vary, but the most popular are viola, guitar, rabeca (violin) and sanfona (accordion). A current variant of desafio is known as repente.

Embolada: northeastern song and dance characterized by rapid, perpetual-motion melody, frequent refrains, and alliterative, sometimes improvised lyrics with comic, satiric, or descriptive content. The danced form is known as coco de embolada.

Favela: hilltop slum; many of the major samba schools in Rio de Janeiro were established in favelas.

Frevo: street and ballroom dance from Pernambuco, possessing a syncopated march-like rhythm of violent and frenetic nature.

Jangada: traditional fishing sailboat of the Brazilian northeast.

Jangadeiro: a jangada sailor.

Jongo: type of samba, sung by one or more soloists, with choral refrain, accompanied by percussion (tambu, candongueiro, gazunga, etc.). The dance moves in an anti-clockwise circle, with the dancers (alone or in pairs) competing in turns in the center.

Macumba: Afro-Brazilian religion elaborated in Rio de Janeiro by descendants of slaves; also the music performed during macumba rites.

Macumbeiro: one who practices macumba.

Malandro: bohemian figure of questionable character but great charm.

Maracatu: carnaval group from Pernambuco featuring a small percussive orchestra, call-and-response singing, and unchoreorgraphed street dancing; a relic of African processions. Also the music performed de such a group.

Marcha de rancho: carnaval march, originally performed by ranchos.

Maxixe: first genuinely Brazilian dance; a fusion of tango, habanera, and polka.

Modinha: old-fashioned lyrical, sentimental song of Portuguese derivation.

Morro: hill; in the context of samba, a hill on which there is a favela.

Orixá: spiritual entity; divine intermediary between God and humans.

Pai-de-santo: spirit father; head of a terreiro who officiates at Afro-Brazilian religious ceremonies.

Partido alto: improvised samba, characterized by call-and-response singing and on-the-spot versifying.

Pastoras: feminine chorus in samba. The name is a holdover from the days of the ranchos and their pastoral themes.

Pernada: a samba game similar to capoeira, in which two opponents dance, attempting to distract and trip each other with the leg.

Quadra: a samba school’s meeting and rehearsal hall; also known as terreiro.

Rancho: old-fashioned type of carnaval group, inspired by Bahian Christmas parades and incorporating pastoral motifs. Until the 1950s, ranchos were larger and more important than samba schools.

Roda de batucada: batucada circle, where two opponents compete in improvising verses or in the physical game of pernada.

Roda de samba: samba circle; an informal gathering where samba is communally sung and played; also known as pagode.

Samba-canção: samba with melodic emphasis; often romantic and sentimental.

Samba de breque: samba in which short breaks are inserted for the purpose of improvising lyrics.

Samba do morro: authentic samba of the favelas and their samba schools.

Samba de roda: samba that is played in a roda de samba.

Samba de terreiro: mid-year (i.e., non-carnaval) samba as performed in a samba school’s quadra. Also known as samba de quadra.

Sebo: used book or record store.

Terreiro: place of worship for Afro-Brazilian religions such as candomblé and macumba (also a synonym for quadra, a samba school’s rehearsal hall).

Toada: old-fashioned, melancholy and sentimental song, usually consisting of one stanza and a refrain.__________________________________________

Recommended reading

Marília T. Barboza da Silva and Arthur L. de Oliveira Filho: Filho de Ogum Bexiguento (Rio de Janeiro, MEC/Funarte, 1979/Gryphus, 1997).

Marília T. Barboza da Silva and Arthur L. de Oliveira Filho: Cartola—Os Tempos Idos (Rio de Janeiro, Funarte, 1983, 1987, 1997/Gryphus, 2003).

Sérgio Cabral: As Escolas de Samba do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro, Lumiar Editora, 1996).

Sérgio Cabral: Pixinguinha, Vida e Obra (Rio de Janeiro, Lumiar Editora, 1997).

Abel Cardoso Junior: Liner notes for the CD Cartola—O Sol Nascerá (Revivendo RVCD-131, 1998).Note: Alexandre Dias scanned the following photographs from the cover of the Native Brazilian Music LP (Museu Villa-Lobos, 1987): Stokowski with Donga & Villa-Lobos; Zé Espinguela; Zé da Zilda; Jararaca & Ratinho; Luiz Americano.

Copyright © 2000–2025 Daniella Thompson. All rights reserved.