The Boeuf chronicles, Pt. 24

Of Italian immigrants & the cinema.

18 October 2002

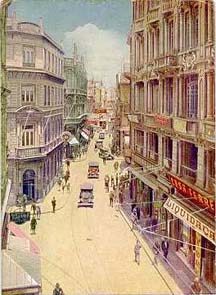

Rua São Bento, in the Triangle of São PauloSão Paulo was defined to a large degree by the Italian immigration of the 19th century. The city’s musical life in particular was marked by the presence of Italians and their descendants. Among paulista erudite composers of Italian origin, one need only mention Francisco Mignone, Camargo Guarnieri, and Lina Pesce. Among music publishers: A. Di Franco, Campassi & Camin, Irmãos Vitale. Musical instrument manufacturers: Giannini, Del Vecchio, and Di Giorgio. Music professors: Luigi Chiaffarelli, Giulio Bastiani, Guido Rocchi, Giacomo Foschini, and Agostinho Cantu. Arranger-conductors: Leo Peracchi, Lyrio Panicali, and Júlio Medaglia. Popular composers and performers: guitarists Américo Jacomino (the first “Canhoto”) and Antônio Rago; sambista Adoniran Barbosa; flutist Copinha; radio queen Marlene; singers Paraguassú, Francisco Petrônio, and Zizi Possi; composer-guitarist-vocalist Toquinho; pianist-composer (and Noel Rosa’s partner) Vadico, and biologist-sambista Paulo Vanzolini.

An important paulista musician born in the old country was Carlos Pagliuchi (1885–1963). He was a pianist of renown and conducted orchestras in various São Paulo cinemas at a time when this was considered a prestigious occupation. In 1917 he became a music professor at the Conservatório Dramático e Musical de São Paulo, abandoning the cinema life.

In his memoir Moto Perpétuo (1982), composer João de Souza Lima, the author of “Amor Avacalhado,” recalled his friendship with Carlos Pagliuchi:

At that time all the cinemas were obliged to maintain a small musical ensemble to accompany the films. One of these establishments, the cinema Pathé Palace, had an ensemble of great importance that was conducted by the musician Carlos Pagliuchi, a great friend, one of the most prominent popular music composers in the city. Who doesn’t remember two of his principal compositions, the waltz “Deusa” and the tango “Estragadão”? When I revealed to him my desire to enter that activity, to play in small ensembles and conduct them as he did, he immediately initiated me. He made me sit at his side to observe how everything was done. It didn’t take long before I adapted to that activity, so much so that I soon became his substitute. [...] I worked in various cinemas of the city: Cine Marconi, Cinema Central (where I had a much larger ensemble), Teatro Esperia (where I worked from its inauguration), today Teatro Bela Vista. [...]

Cine Central in São Paulo,

a choice musical venueFollowing a frenetic work schedule, Souza Lima became exhausted and went to recover his health in the tranquil town of Tremembé. There he was visited by friends from São Paulo:

One of these visits was made by my great friends Waldemar Otero and Carlos Pagliuchi. The latter, very jovial, went out one fine day with his camera to the streets of that little town, posing as a professional photographer, dragging his steps and yelling: “special portraits at ten cents a dozen; ugly subjects come out beautiful; black come out white,” and other such things. We died of laughter. And when, at night, he and Waldemar Otero climbed the trees in the garden and played their little mouth organs, people who strolled by didn’t know where the music came from!

Pagliuchi produced a goodly number of both popular and erudite compositions. Manoel Aranha Corrêa do Lago discloses that Pagliuchi was one of the composers—the others were Alberto Nepomuceno, Henrique Oswald, Francisco Braga, and Xavier Leroux—chosen by José de Freitas Valle (“Jacques d’Avray”) to set his Tragi-Poèmes to music. Pagliuchi’s Le Clown for voice and orchestra was performed in São Paulo under the baton of Xavier Leroux, who had been one of Milhaud’s teachers at the Paris Conservatoire. The music library of the Instituto de Estudos da Cultura Musical do Mundo de Língua Portuguesa (based in Cologne, Germany) lists Pagliuchi’s popular compositions “Raggi infrarossi”; “Encrenca”; “Noite de Santo Antonio”; “Noite de São Paulo”; “Noite de São Pedro”; “Urucubaca”; and “Sertanejo”—all published by A. Di Franco of São Paulo—and his “Estragadão,” published by C. M. Roehr.

Rua Direita, in the Triangle of São PauloTune No. 24: “Sertanejo” (1919)

In its original piano score, “Sertanejo” is identified as both a tango and a batuque-dança brasileira. It’s a complicated piece to play, seeming to require twice the ordinary number of fingers, if the proliferation of notes on the page is an accurate indication.

The composition is dedicated “Ao Dist. e insuperavel amigo Paulo Pereira Barretto.” Might this dedicatee be a relative of Dr. Luiz Pereira Barreto (1840–1923), the illustrious scientist, politician, and journalist?

Fundação Joaquim Nabuco’s database lists a total of two recordings of Pagliuchi’s works, one being “Sertanejo.” The tune had to wait eleven years to be recorded.

Autor: Carlos Pagliuchi

Título: Bréjeira

Gênero: Valsa-Chôro

Intérprete: Orquestra Andreozzi

Gravadora: Odeon

Número: 121605

Fred Figner Collection, courtesy of Rachel Esther Figner SissonAutor: Carlos Pagliuchi

Título: Sertanejo

Gênero: Tango Brasileiro

Intérprete: Orquestra Paulistana

Gravadora: Odeon

Número: 10713-B

Matriz: 3772

Data Lançamento: Dez/1930As discussed in The Boeuf chronicles, Pt. 23, the “Sertanejo” quotation in Le Boeuf sur le Toit is part of a three-tune counterpoint. Milhaud quotes section C of “Sertanejo” before section A. The former begins at 13:19 min. into Louis de Froment’s recording.

Section A begins about 15 seconds later but is practically inaudible under the trumpets playing “Seu Amaro Quer.” The same section can be heard quite clearly in the piano four-hands recording by Stephen Coombs & Artur Pizarro.

Stephen Coombs and Artur Pizarro play MilhaudAs the Orquestra Paulistana recording of “Sertanejo” isn’t available, Alexandre Dias recorded section C

and section A from the original piano score.

Scan courtesy of Alexandre Dias

Copyright © 2002–2016 Daniella Thompson. All rights reserved.