The Boeuf chronicles, Pt. 30

Milhaud, his diplomat librettists,

17 October 2003

and the influence of Brazil.

Paul Claudel, Henri Hoppenot & Darius Milhaud in Rio

(photo courtesy of Antonio Campos)In his autobiography Notes Without Music, Darius Milhaud related the circumstances that resulted in his coming to Brazil during WWI:

I was rejected for military service on medical grounds. [...] I left the Foyer Franco-Belge to work at the Maison de la Presse, grouped with the propaganda services directed by Philippe Berthelot, and therefore came under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I was sworn into the Army, and attached to the Army photographic service. I made friends with a number of young diplomatists. We used to meet occasionally in a restaurant in the Place Gaillon. We had delightful meals, enlivened by the spicy anecdotes of Paul Morand and René Chalupt, the musician-poet, and by Saint-Léger Léger’s tales of the West Indies, to all of which Henri Hoppenot and I listened in silence. I had just finished my Poèmes juifs, settings for some anonymous poems I had come across in a revue, and I was seriously thinking of composing music for Les Euménides in Claudel’s translation. I mentioned it to him one day when I met him at the Maison de la Presse. He complained of having too much to do at Rome; he needed a secretary, and proposed that I should get Berthelot to send me there on detachment. Before the scheme could materialize, however, he was appointed Minister to Brazil. He renewed his request, and the idea of going with him so far away, and the great longing for solitude I had felt since Léo’s death, made me decide to accept.

At the end of December, my parents and my friend Yvonne Giraud accompanied the great man and his ‘secretary’ to the Gare d’Orsay.

The crossing took eighteen days. [...] We reached Rio on February 1st, 1917, on a blazing hot day like midsummer. Claudel found quarters for me with him at the French legation; magnificently situated in the Rua Paysandu, a street bordered with royal palms from the isle of Réunion sometimes more than two hundred feet in height and crowned with swaying fronds over twenty feet long. [...]

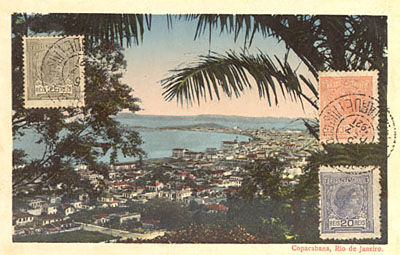

The palm-lined Rua PaissanduRio had a potent charm. It is difficult to describe the lovely bay, ringed with fantastically shaped mountains covered with a light shading of forest or crowned with solitary red-brown pinnacles of rock, sometimes topped with lines of palm-trees that stood out like ostrich feathers in the murky light of the tropics against a sky shrouded in pearly grey cloud. I would often stroll in the centre of the city where—a refreshing contrast with the broad Avenida Rio Branco—the cool, shady streets were too narrow for wheeled traffic. In the most colourful of them all, the Rua Ouvidor, antique shops crowded with furniture from the Imperial period stood next to displays of luscious fruit where I tasted delicious refrescos of mango or coconut. Not far away, on a hill, the little Gloria church, eighteenth-century baroque in style, like most of the ecclesiastical architecture in Brazil, displayed its colors of pink, blue and tender green, and its azulejos among which were to be seen magnificent examples of wood carvings. I would also sometimes go to Copacabana beach, facing the Atlantic. Along it stood a few houses, including one delightfuly amusing by the architect Virzi. In the evenings I often walked around the Tijuca. I loved to see the panorama of Rio gradually spread out before me, with the bay clearly outlined in glittering lights; or else I would take a boat to the other side of the bay, near Nichteroy, and lie on the lonely beach for a whole part of the night with the moonlight so bright that I could read easily.

Copacabana in 1921A month or two after our arrival in Rio, Henri Hoppenot was appointed secretary to the Legation. Overjoyed, I went to the boat to meet him and his wife Hélène. Already I felt how much their presence was going to mean to me. Henri Hoppenot was a young writer and a great admirer of Claudel. What a curious legation that was, with two writers and a musician... During our long walks together we got to know one another better and our friendship deepened.

The friendship with the Hoppenots turned into a life-long affair. Milhaud dedicated to them two dances in Saudades do Brazil: “Corcovado” for Madame Henri Hoppenot, “Sumaré” for her husband (Paul Claudel was the dedicatee of “Paysandu”).

Henri Hoppenot (1891–1977) went on to become one of France’s most illustrious diplomats. Seemingly always posted to the hot spots, in 1943 Hoppenot was the Provisionary Government of the French Republic’s ambassador to Washington. From there he was dispatched to Martinique, where he assumed control of the French Antilles from the Vichy government on behalf of Free France. In the early 1950s, he was France’s ambassador to the United Nations and its representative on the Security Council. It was there, on 31 March 1953, that Hoppenot formally proposed the name of the Swedish Minister of State, Dag Hammarskjöld, for the position of U.N. Secretary-General. In 1955 Hoppenot was ambassador to Vietnam, at a time France was eager to remove its forces from that country and into North Africa. By 1958 Hoppenot himself had been posted to Algeria, at the time of the Algérie française referendum.

In 1951, the Hoppenots published the photographic book Extrême-Orient, with photos by Hélène and texts by Henri. But even earlier, Hoppenot wrote three libretti for Milhaud’s Opéras-minute. Recalled the composer in his autobiography:

Between 1922 and 1932 Paul Hindemith was organizing concerts of contemporary music, first at Donaueschingen under the patronage of the Prince of Fürstenberg, and then in Baden-Baden under the auspices of the municipal authorities, and finally in 1930 in Berlin. Hindemith was absolutely his own master, and he tried out all kinds of musical experiments. In 1927 he asked me to write an opera, which had to be as short as possible. Henri Hoppenot wrote a libretto for me, on the subject of L’Enlèvement d’Europe, off-handed, poetic, and slightly ironic in its treatment, and containing all the essential elements on a miniature scale. It was produced in conjunction with Die Prinzessin auf der Erbst by Toch, lasting one hour, Kurt Weill’s Mahagonny lasting 30 minutes, and Hindemith’s Hin und Zurück, lasting fourteen minutes. Emil Hertzka, the managing director of Universal-Edition, did not consider the publication of my work to be a commercial proposition: “What an idea, an opera that lasts only nine minutes!” “Now,” said he, “if you would only write me a trilogy...” Once more I had recourse to Henri Hoppenot, who in spite of his official duties (at that time he occupied a post in Berlin) dashed off two more librettos of the same kind as the previous one: L’Abandon d’Ariane and La Délivrance de Thésée. The three operas together lasted twenty-seven minutes. The trilogy was immediately produced at the Operas of Wiesbaden and Budapest, and I did a recording for Columbia. I have never been able to understand why the firm did not make more publicity of the fact that each opera only occupied one disc.Other Milhaud compositions born of his connection with Hoppenot were La Libération des Antilles and Le Bal Martiniquais. As Milhaud recalled it:Shortly after the landings in North Africa, Henri Hoppenot, who represented the Algiers Committee in Washington, was placed in charge of the operations for the liberation of the Antilles. He went there on a warship, was acclaimed by the Gaullist population and received the capitulation of Admiral Robert. In local folklore, the name of Hoppenot is now honored like that of an angel of deliverance. The Governor sent me some musical material which he thought might interest me and some popular melodies which I used in La Libération des Antilles. I could not resist using the popular songs which included works like: ‘Mawning, Massa Minister Hoppenot...’ I used the same material in Le Bal Martiniquais for two pianos, which I later arranged for orchestra.

Milhaud’s friendship with Paul Claudel (1868–1955) preceded his Hoppenot connection by five years. In 1911, the composer first encountered Claudel’s poetry and immediately set some poems to music. Claudel became one of his three favorite authors, along with Francis Jammes and André Gide. The following year, when Milhaud was 20, the two met. “Between Claudel and myself,” Milhaud would write years later, “understanding was immediate, our mutual confidence absolute.” Their friendship and artistic collaboration lasted until the poet’s death. Their 368-page correspondence between 1912 and 1953 was published by Gallimard in 1961 with a preface by Hoppenot.

Although both poet-diplomats served in Brazil with Milhaud, none of their collaborations took on Brazilian character. In his unpublished article Influence of Latin-American music on my work, written at Mills College in 1944, the composer reminisced:

The two years which I spent in Brazil with Claudel were glorious. In the first place, I had the leisure to study the folklore of this country, to attune myself to the rhythms of the tangos, maxixes and sambas, to the melancholy of the Portuguese fados. I could watch the Carnival balls of the Negroes and could assimilate gradually the curves of these rhythms which [are] as supple as the huge leaves of the royal palms swaying at the height of sixty meters.

However, the Brazilian influence would not become evident in his work until 1919, after he had returned to Paris and composed Le Boeuf sur le Toit. His first musical work in Brazil was the final installment in his Orestie trilogy, consisting of two works for chorus & orchestra and an opera, based on the tragedies by Aeschylus in Claudel’s translation. Milhaud had composed Agamemnon, op. 14 in 1913–14 and Les Choëphores, op. 24 in 1915–16. In Notes Without Music he described the creation of the opera, op. 41:

As soon as I arrived in Rio, I started work on Les Euménides. In Les Choëphores I had used chords superimposed in masses; the nature of the musical thought in Les Euménides led me to adopt the same device.

Claudel, Milhaud & Hoppenot riding horseback in Brazil

(from Paul Collaer: “Darius Milhaud”)While in Rio, Claudel wrote the poème plastique “L’Homme e son Desir,” which Milhaud would set to music for a ballet by the same title, his op. 48. Also born in Rio was Dans les rues de Rio, op. 44a (1918), a mini-suite of two songs based on Claudel’s poems “Le Rémouleur” (The Knife Sharpener) and “Le Marchand de Sorbets” (The Ice Cream Seller), which were a follow-up to the suite Chansons Bas, op. 44 (1917), eight melodies on poems by Stéphane Mallarmé, all describing various tradesmen. Claudel’s satiric drama Protée gave rise to Milhaud’s incidental music, op. 17 (1913–17). In the 1920s and ’40s Milhaud would set eleven Claudel poems to music. The poet and the composer would go on to collaborate on other creations, including the opera Christophe Colomb, op. 102 and the cantatas Cantate de la paix, op. 166 and Invocation à l’ange Raphaël, op. 395.

As for the Brazilian influence on Milhaud’s music, that too lasted for many years, albeit intermittently. Following Le Boeuf sur le Toit (1919) came Saudades do Brazil for piano solo, op. 67 (1920) and for orchestra, op. 67b (1920–21), a suite of dances bearing the names of Rio districts and dedicated to various friends the composer knew in Brazil:

- Sorocaba (pour Madame Regis de Oliveira)

- Botafogo (pour Oswald Guerra)

- Leme (pour Nininha Velloso-Guerra)

- Copacabana (pour Godofredo Leão Velloso)

- Ipanema (pour Arthur Rubinstein)

- Gávea (pour Madame Henrique Oswald)

- Corcovado (pour Madame Henri Hoppenot)

- Tijuca (pour Ricardo Vines)

- Sumaré (pour Henri Hoppenot)

- Paineras (pour La Baronne Frachon)

- Laranjeiras (pour Audrey Parr)

- Paysandu (pour Paul Claudel)

In 1926, he reutilized Alberto Nepomuceno’s “Galhofeira,” this time inserting it into “Souvenir de Rio,” part XI of Le Carnaval d’Aix, Op. 83b for piano and orchestra.

In 1937 Milhaud composed

[...] a piano work that gave me enormous trouble. It was a suite for two pianos, to be played by Ida Jankelevitch and Marcelle Meyer. I took some passages from two sets of incidental music for the stage, and called the mixture Scaramouche. At once Deiss offered to publish it. I advised him against it, saying that no one would want to buy it. But he was an original character who only published works that he liked. He happened to like Scaramouche and insisted on having his way. In the event he was right, for while sales of printed music were everywhere encountering difficulties, several printings were made, and Deiss took special delight in informing me: ‘The Americans are asking for 500 copies and 1000 are being asked for elsewhere.’

Scaramouche is a suite in three mouvements: Vif, Modéré, and Brazileira. What Milhaud doesn’t tell us is that it was commissioned by Ida Jankelevitch for a performance at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair (Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne). It became so popular that Milhaud arranged it for saxophone and orchestra. In the composition of Scaramouche, Milhaud used music he had written to accompany the Molière comedy Le Médecin Volant. The protagonist of this play is Sganarelle, a scheming valet who pretends to be a physician. He is based on the Commedia dell’Arte stock character Scaramouche (or Scaramuccia), an unscrupulous and unreliable servant. His affinity for intrigue often lands him in difficult situations, yet he always manages to extricate himself. Saxophonist Sarah Kerbeshian opines that the title of Milhaud’s suite evokes the multiplicity of possible interpretations of the music, just as the personage of Scaramouche displays more than one character. Polytonality traverses all the movements of Scaramouche, expressing the theme of simultaneity, with several points of view seen at the same time.

For choro lovers, it is interesting to note that the third movement of Scaramouche, “Brazileira,” bears a striking resemblance to Pixinguinha’s “Ainda Me Recordo,” and its opening sounds eerily like the tango “Brejeiro” by Ernesto Nazareth.

Milhaud himself recorded Scaramouche, op. 165b with Marcelle Meyer in 1938. In 1945 he composed Danses de Jacarémirim, op. 256 for violin & piano, comprising the three parts “Sambinha,” “Tanguinho,” and “Chorinho.” Jacarémirim was the pseudonym the composer had used in his article titled “Le Boeuf sur le Toit (Samba carnavalesque)” and published in the April 1919 issue of Littérature. The article described carnaval in Rio and concluded thus:

Il y a beaucoup à apprendre de ces rhythmes mouvementés de ces mélodies que l’on recommence toute la nuit et dont la grandeur vient de la monotonie. J’écrirai puet-être un ballet sur le carnaval à Rio qui s’appellera “Le Boeuf sur le Toit”, du nomme de cette samba que la musique jouait ce soir pendant que dansaient les négresses vêtues de bleu.There is a lot to learn in the lively rhythms of these melodies that are played over and over all night long and all whose greatness comes from monotony. Perhaps I’ll write a ballet about the carnaval in Rio that will be called “Le Boeuf sur le Toit,” from the name of this samba that they played this evening while the negresses dressed in blue danced.In his 60s, Milhaud returned to Brazil in the suite Le Globetrotter, op. 358 for piano solo or chamber ensemble (1956–57). It is a vivacious set of travel snapshots depicting France, Portugal, Italy, the United States, Mexico, and Brazil. The composer was equally loyal to the places he had known as he was to his friends.

Copyright © 2003–2016 Daniella Thompson. All rights reserved.