Praça Onze in Popular Song, Pt. 1

A place of the imagination.

12 June 2003

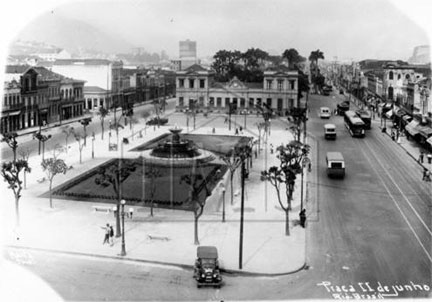

Praça Onze by Augusto MaltaHas there ever been a public space in Brazil more emblematic than Praça Onze de Junho?

This defunct square at the heart of the Cidade Nova in Rio de Janeiro is celebrated as the birthplace of the maxixe and the samba and one of the cradles of choro.

It was here that “Pelo Telefone” was composed.

It was here that the escolas de samba first began parading at carnaval.

It is here that the Passarela do Samba (aka Sambódromo) and the Terreirão do Samba are located, in a vast wasteland of urban decay.No other square is lauded or mourned in so many popular songs.

Yet the entire history of this cherished spot comprises no more than ninety years.The physical square is gone, but its spirit remains. This is the first vignette in a series that may become a concise history of a place that lives on in the imagination.

“Boêmios” by Heitor dos PrazeresThe first recorded song ever to mention Praça Onze was most likely the cançoneta “Não Empurre” (author unknown), which was released on disc as soon as the gramophone was introduced in Brazil, in 1902. Its debut recording, no. 10005 on the Zon-O-Phone label, was in effect the fifth Brazilian record ever released. The second, Zon-O-Phone X-532, is not dated but could have been a second edition of the same recording. By 1911 or 1912, there was a third recording, this one made by the famous Bahiano on Odeon disc no. 108527. Then the cançoneta was shelved until 1999, when Maricenne Costa resurrected it in her disc of ‘firsts,’ Como Tem Passado!! (CPC-UMES 026).

Bahiano“Não Empurre” is a rather lewd story taking place in the Cidade Nova. The storyline includes an eventful bonde ride. It begins:

Tomei o bonde da Carris Urbanos,

Desses que vão até a Praça Onze,

Mas a meu lado, dois olhos maganos

Me perguntaram se eu era de bronze.

Então, para provar que eu não era,

Quis eu logo fazer coisa limpa,

Pois eu nessas coisas sou cuera,

Sou mesmo supimpa.Then the narrator relates how, when the bonde turned a corner, he contrived to fall on the young woman by his side. She naturally complained, in double entendre that would make even a malandro blush:

Não empurre, não empurre

Seu Manduca,

Vê que assim me remói,

Não empurre, não empurre

Que machuca,

Não empurre assim que dói...Bahiano’s 1912 recording was sent to me by the collector Dijalma M. Candido, who noted that this type of almost-pornographic cançoneta was a staple of Casa Edison’s repertoire in the early years of the 20th century. Whoever heard Mário Pinheiro’s recordings of “A Boceta de Rapé” or “Pela Porta de Detrás” would not hesitate to agree with Dijalma’s assessment.

“Não Empurre” must have had a measure of commercial success to have been released three times within a decade. At the time it came out, Praça Onze was known chiefly as a center of cheap entertainment, the hangout of malandros and prostitutes, where men of the better classes went unaccompanied by their wives.

The birth of “Pelo Telefone” in Praça Onze appears to have gone unremarked in the popular song of the day. By the time Sinhô mentioned the Cidade Nova in “A Favela Vai Abaixo” of 1928, (“Vou morar na Cidade Nova pra voltar meu coração para o morro da Favela”), the first samba schools were being established. Within a few years, they would bring their carnaval parades to Praça Onze, but even earlier, rodas de samba and batucada or pernada contests were a common sight in the square, principally because a public scale was located there, and all carters arriving from the nearby port had to have their cargos weighed. While awaiting their turn, they passed the time clapping, singing, and dancing or fighting.

Launched a year before Mário Filho’s short-lived newspaper Mundo Esportivo would sponsor the first samba-school carnaval parade in the square, the samba amaxixado “Na Praça Onze” was a typically carefree malandro manifesto, swearing off any tenderness toward the opposite sex. Praça Onze is presented as the place where the protagonist joined a roda de samba, pandeiro in hand, and came out a certified bamba.

Na Praça Onze

(Francisco Gonçalves de Oliveira; 1930)Sou enfezado

Eu sou mesmo da coroa

E essa gente da Gamboa

Só me olha com respeito

Não tenho amor

Minha amante é a navalha

Eu sou filho da canalha

Para amar, não tenho jeito

Na Praça Onze de Junho

Entrei na roda de um samba

Com o meu pandeiro em punho

Eu tirei carta de bamba [bis]

A minha sina

É viver assim sozinho

E ter raiva do carinho

De qualquer bicho de saia

Por isso mesmo

Eu procuro a minha morte

Eu sou filho da gandaia

No amor não tenho sorte

Na Praça Onze de Junho

Entrei na roda de um samba

Com o meu pandeiro em punho

Eu tirei carta de bamba [bis]Samba recorded by Teobaldo Marques da Gama

and released on Parlophon 13260-A in January 1931.

Moreira da Silva

Image courtesy of Dijalma M. CandidoIn 1932, the journalist Mário Filho (Maracanã stadium is named after him), editor of the newspaper O Mundo Sportivo, organized the first carnaval parade of the escolas de samba. Carnaval parades traditionally took place on Avenida Rio Branco. However, the avenue was reserved for the corso on Sunday, the ranchos on Monday, and the grandes sociedades on Tuesday. The escolas, therefore, took to Praça Onze, where the parade progressed along Rua Senador Eusébio, then crossed through Marquês de Pombal, concluding at Rua Visconde de Itaúna. The first parade competition occurred on 7 February 1932. It was such a success that the following year, following the demise of O Mundo Sportivo, the newspaper O Globo assumed the sponsorship.

At the carnaval of 1933, the foliões heard “Oi, Maria!,” which appears to have been the first samba by Assis Valente that included a mention of Praça Onze. This song was written especially for the carnaval, making allusions to cordão, estandarte, folia, and fantasia. The recording was made by Benedito Lacerda’s first conjunto regional, Gente do Morro, with the young Moreira da Silva fronting as vocalist.

Oi, Maria!

(Assis Valente, 1932)Oi Maria!

Samba de noite e de dia

Oi Maria!

Samba de noite e de dia

A madrinha do cordão

tem a pele cor de bronze

Vem a pé de Deodoro

segurando o estandarte

pra dançar na Praça Onze

Oi Maria!

Samba de noite e de dia

Oi Maria!

Samba de noite e de dia

Meu avô é português

e gosta muito da folia

Fica de cabeça inchada

quando vê na batucada

a crioula da Bahia

Oi Maria!

Samba de noite e de dia

Oi Maria!

Samba de noite e de dia

Minha avó é bem velhinha

do tempo da Monarquia

Quando entra na virada

vai dizendo a todo mundo

que velhice é fantasia

Oi Maria!

Samba de noite e de dia

Oi Maria!

Samba de noite e de dia

Quando vem o Carnaval

não quero amofinação

É o céu meu cobertor

Praça Quinze é meu chatô

O gramado é meu colchão

Oi Maria!

Samba de noite e de dia

Oi Maria!

Samba de noite e de diaSamba recorded by Gente do Morro with vocalist Moreira da Silva on 13 December 1932 and released on Victor 33612-B in January 1933.

Carmen Miranda

Image courtesy of Dijalma M. CandidoIn contrast with the malandro boast of “Na Praça Onze,” the character in “Ao Voltar do Samba” yearns for love, but things haven’t turned out exactly as she’d hoped. In this case, the abandoned woman turns the tables on her cheating lover, and now he is the one who suffers while she gloats in revenge. Once again, Praça Onze is depicted as a party place, where the heroine took part in a batucada—a year following the first city-sanctioned carnaval parade.

The song’s original title was “Arlequim de Bronze.” According to Abel Cardoso Junior, Ary Barroso claimed to Synval Sylva that he had thought of this title for one of his own compositions, so Carmen Miranda recorded it under the title “Ao Voltar do Samba.” When Clara Nunes recorded this samba in 1973, she reverted to the original title.

Ao Voltar do Samba

(Synval Silva; 1934)Oh Deus

Eu me acho tão cansada

Ao voltar da batucada

Que tomei parte lá na Praça Onze

Ganhei no samba um arlequim de bronze

Minha sandália quebrou o salto

E eu perdi o meu mulato

Lá no asfalto

Eu não me interessei em saber

Alguém veio me dizer

Que encontrou você se lastimando

Com lágrimas nos olhos, chorando

Chora mulato, meu prazer é de te ver sofrer

Para saber quanto eu te amei

E quanto eu sofri para te esquecer

Agora chora mulato, meu prazer é de te ver sofrer

Para saber quanto eu te amei

E quanto eu sofri para te esquecer

Oh Deus

Eu me acho tão cansada...

Eu tive amizade a você

Eu mesmo não sei porquê

Eu conheci você na roda, sambando

Com tamborim na mão, marcando

Agora mulato por você não faço desacato

Eu vou à forra e comigo tem

Ora se tem

Ou este ano ou pro ano que vemSamba recorded by Carmen Miranda & Grupo do Canhôto

on 26 March 1934 and released on Victor 33808-A in August 1934.

Aurora Miranda

Image courtesy of Dijalma M. CandidoWhile Synval Silva was furnishing a Praca Onze–related song to Carmen Miranda, Custódio Mesquita was doing the same for Carmen’s sister, Aurora, who the previous year had made a big hit of his marcha “Se a Lua Contasse.”

In “Moreno Cor de Bronze,” Custódio extols the virtues of the mulatto born in Praça Onze as a master of samba, style, and love—the ultimate Brazilian. “Your color is worth more than a treasure,” proclaims the (white) author, “Because of you, bronze is worth more than gold.” This stance stood in marked contrast with Brazilian society’s prevailing prejudices. Its bite was mitigated by being sung as a love song.

Moreno Cor de Bronze

(Custódio Mesquita; 1934)Moreno cor de bronze

Que nasceu na Praça Onze

E se diplomou em samba

Na academia do Salgueiro

Tem na cor a faceirice

Tem na voz toda a meiguice

Própria de um brasileiro

Não há nada, moreno

Que se compare a você

Teu amor é mais gostoso

É melhor o teu querer

Tua cor é maravilha

E vale mais que um tesouro

Por sua causa, moreno

O bronze vale mais que o ouroSamba-canção recorded by Aurora Miranda with Simon Bountman & Orchestra

Odeon on 19 April 1934 and released on Odeon 11125-A in June 1934.= = =

By the time the sentimental torch song “Foi na Praça Onze” came out, Praça Onze was established as Rio de Janeiro’s official carnaval parade ground for samba schools. The ranchos and grandes sociedades continued to parade uptown in the far more elegant Avenida Rio Branco. The hero of the samba below bears no bitterness or malice toward the popular morena from Mangueira whom he’d met at Praça Onze and who ignores him.

Foi na Praça Onze

(Max Bulhões/Milton de Oliveira; 1937)Foi na Praça Onze

Que eu te conheci sambando

A gargalhar...

Vou lembrando aquele dia

Em que cheio de alegria

Quis amor te declarar

Rindo e cantando,

Mandaste esperar...

Sei que nasceste em Mangueira

E sendo morena faceira

És a mais querida mulher do lugar

Se eu sofro do coração

Porque não me dás atenção

Deixa um minuto sequer te amarSamba recorded by Fausto Paranhos on 22 March 1937

and released on Victor 34166-B in May 1937.

Bando da LuaAssis Valente returned to Praça Onze in 1937. The protagonist of his samba carnavalesco “Cansado de Sambar” was born in Praça Onze, and that, no doubt, is why s/he lives to sambar. The birth in the consecrated plaza confers special ability and legitimacy worthy of a presidential decoration.

Cansado de Sambar

(Assis Valente; 1937)Tenho o corpo cansado de sambar

Noite e dia (cansado de sambar)

Tenho o corpo cansado de sambar

Noite e dia

Perguntei ao coração se queria descansar

Ele disse que não, que não queria

Perguntei ao coração se queria descansar

Ele disse que não, não, não

Eu nasci na Praça Onze

Dou a vida pra sambar

Já sambei lá na Favela

Salgueiro e Portela

Estácio de Sá

Vou sambar lá em Brasilia

Pro Seu Presidente

Me condecorar

(Vamo lá)

Já sambei no Amazonas, Pernambuco e Macaé

Vou sambar com a paulista, morena faceira

Do Largo da Sé

A paulista bronzeada, morena queimada

Cheirando a café

(A café)Samba recorded by Bando da Lua on 3 December 1936 and released on Victor 34133-B in January 1937.

When Bando da Lua recorded the song again in 1941, this time in the United States, Uncle Sam made an appearance in the lyrics, with a reference to Carmen Miranda’s success in North America in her baiana costume. Favela became Deodoro and Portela tunred into Mangueira.

Tenho o corpo cansado de sambar

Noite e dia (cansado de sambar)

Tenho o corpo cansado de sambar

Noite e dia

Perguntei ao coração se queria descansar

Ele disse que não, que não queria

Perguntei ao coração se queria descansar

Ele disse que não, não, não

Eu nasci na Praça Onze

Dou a vida pra sambar

Já sambei em Deodoro

Salgueiro e Mangueira

Estácio de Sá

Vou sambar lá no Catete

Pro Seu Presidente

Me condecorar

(Vamo lá)

Já sambei no Amazonas, Pernambuco e Macaé

Encontrei lá em São Paulo, morena queimada

Cheirando a café

Tio Sam já viu também o torço de seda

Que a baiana tem

(O que é que a baiana tem)Over the ensuing decades, the lyrics of the second part have been adapted to suit the situation. Emilinha Borba omitted all carioca references in her 1950s recording, singing only about Amazonas, Pernambuco, Macaé, and the Largo da Sé in São Paulo.

Recording the song in 1966, after the federal capital had relocated from Rio to Brasília, Aracy de Almeida substituted the new capital’s name for Palácio do Catete, the former presidential residence. Listen to Aracy’s 1966 recording.Tenho o corpo cansado de sambar

Noite e dia (cansado de sambar)

Tenho o corpo cansado de sambar

Noite e dia

Perguntei ao coração se queria descansar

Ele disse que não, que não queria

Perguntei ao coração se queria descansar

Ele disse que não, não, não

Eu nasci na Praça Onze

Dou a vida pra sambar

Já sambei lá na Favela

Salgueiro e Portela

Estácio de Sá

Vou sambar lá em Brasilia

Pro Seu Presidente

Me condecorar

(Vamo lá)

Já sambei no Amazonas, Pernambuco e Macaé

Vou sambar com a paulista, morena faceira

Do Largo da Sé

A paulista bronzeada, morena queimada

Cheirando a café

(A café)Samba recorded by Aracy de Almeida on the LP Samba É Aracy de Almeida (Elenco ME-35; 1966), with arrangements by Roberto Menescal and Ugo Marotta.

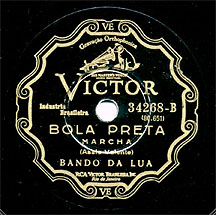

Image courtesy of Dijalma M. CandidoIn a theme by now familiar, “Bola Preta” values black above white, using the game of roulette in an analogy with feminine sexual prowess. When you play roulette, claim the lyrics, only he who plays with the black ball wins. A blond woman is like a ball of soap that can’t withstand agitation. In contrast, the morena is hard and satisfying. Like Custódio Mesquita, Assis Valente talks of skin the color of bronze, which rhymes nicely with Praça Onze, the fount of samba.

Bola Preta(Assis Valente; 1937)Na hora do joguinho da roleta

Só ganha quem jogar na bola preta

Na hora do joguinho da roleta

Só ganha quem jogar na bola preta

A lourinha é uma bola de sabão

Bola que só tem beleza,

não aguenta repuxão

Mas a mulata que é mesmo da coroa

A gente joga e dá bolada

Nunca vi que bola boa

Na hora do joguinho da roleta

Só ganha quem jogar na bola preta

Na hora do joguinho da roleta

Só ganha quem jogar na bola preta

A morena é uma bola cor de bronze

Que dá bola quando samba no jardim da Praça Onze

Mas a crioula parece malacacheta

Ela é dura e dá no couro

Nunca vi que bola pretaMarcha recorded by Bando da Lua on 23 December 1937

and released on Victor 34268-B in January 1938.

Assis ValenteLaunched in 1939, perhaps the greatest single year for Brazilian popular music, “Uva de Caminhão” was a mid-year samba, although it is redolent of the humorous nonsense commonly found in carnaval marchinhas. A closer inspection reveals that the nonsense is carefully planned, for the lyrics are largely made up of the titles of carnaval songs (most of them marchinhas, as it turns out). Perhaps that’s why the song was labeled as ‘samba revista.’ Praça Onze is mentioned only in passing, but the reference once again connects the square to the batucadas that regularly took place there during the 1930s. In the lyrics below, the passages in red are the titles of 1939 carnaval songs, while those in blue cite songs from previous years (see footnotes for details). The story’s point of departure was the composer’s observation of grapes being sold from the back of a truck in Largo da Carioca. On this flimsy base, he inventively constructed the song’s fabulist plotline, which is—if you choose to notice it—rife with sexual innuendo.

Image courtesy of Dijalma M. Candido“Uva de Caminhão” was a big hit for Carmen Miranda, recorded on 21 March 1939 and released in May on Odeon 11712-A. Decades later it was recorded by Wanderlea (in Wanderlea Maravilhosa, 1973), Céu da Boca (in Céu da Boca, 1981), and Clara Sandroni (in Assis Valente, 1986).

Uva de Caminhão

(Assis Valente; 1939)Já me disseram que você andou pintando o sete 1

Andou chupando muita uva e até de caminhão

Agora anda dizendo que está de apendicite 2

Vai entrar no canivete, vai fazer operação

Oi, que tem a Florisbela 3 nas cadeiras dela 4

Andou dizendo que ganhou a flauta de bambu 5

Abandonou a batucada 6 lá da Praça Onze 7

E foi dançar o pirolito 8 lá no Grajaú 9

Caiu o pano da cuíca 10 em boas condições

Apareceu Branca de Neve com os sete anões 11

E na pensão da dona Estela 12 foram farrear

Quebra, quebra gabiroba quero ver quebrar 13

Você no baile dos quarenta deu o que falar

Cantando o Seu Caramuru 14 bota o pajé pra brincar

Tira, não tira o pajé, deixa o pajé farrear

Eu não te dou a chupeta, 15 não adianta chorar

Notes

- pintando o sete is a likely reference to the marcha “Menina Que Pinta o Sete” (Ataulfo Alves/Roberto Martins), recorded by Bando da Lua on Victor 34009-B for the 1936 carnaval. Side A of the same disc carried Assis Valente’s samba “Maria Boa.”

- apendicite was mentioned in the marcha “A Casta Suzana” (Ary Barroso/Alcyr Pires Vermelho), recorded by Déo on Odeon 11690-B and released for the 1939 carnaval.

- “Florisbela”: marcha by Antônio Nássara & Erastótenes Frazão. Recorded by Sílvio Caldas and released on Victor 34387-B in December 1938.

- que tem [...] nas cadeiras dela is a quotation from the batucada “O Que Tem Iaiá” (Germano Augusto/Kid Pepe), recorded by Aracy de Almeida and released on Victor 34258-A in December 1937.

- “Flauta de Bambu”: marcha by Antônio Nássara & Sá Roris. Recorded by Jararaca and released on Odeon 11691-A in February 1939.

- Abandonou a batucada is a reference to “Adeus Batucada,” samba by Synval Silva, recorded by Carmen Miranda and released on Odeon 11285-A in November 1935. Two months after the release of “Uva de Caminhão,” Castro Barbosa would release “Morreu a Batucada,” samba by Saint Clair Senna.

- lá da Praça Onze is a quotation from “Ao Voltar do Samba” by Synval Silva, recorded by Carmen Miranda in 1934 (see lyrics further up the page).

- “Pirolito”: marcha by João de Barro & Alberto Ribeiro. Recorded by Nilton Paz & Emilinha Borba on 3 January 1939 and released on Columbia 55.013-A in February 1939. Carmen Miranda & Almirante would perform this song on stage and in the film Banana da Terra.

- “No Grajaú, Iaiá”: samba by J. Francisco de Freitas & Dan Malio Carneiro. Recorded by Mario Reis and released on Odeon 10576-A in March 1930. It was one of several songs hastily brought out in order to bank on the success of “Na Pavuna” (Homero Dornellas/Almirante).

- “Caiu o Pano da Cuíca”: marcha by Haroldo Lobo & Milton de Oliveira. Recorded by Patrício Teixeira on 25 November 1938 and released on Victor 34404-A in January 1939.

- “Branca de Neve”: marcha by Benedito Lacerda & Herivelto Martins. Recorded by Trio de Ouro on 24 November 1938 and released on Odeon 11696-A in February 1939. That year, Disney received the Oscar for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

- “Na Pensão da Dona Estela”: marcha by Paulo Barbosa & Oswaldo Santiago. Recorded by Carmen Miranda & Barbosa Jr. on 22 November 1938 and released on Odeon 11694-B in January 1939.

- “Quebra, Quebra Gabiroba”: marcha by Plínio Brito. Recorded by Januário de Oliveira and released on Columbia 5.183-B in March 1930.

- “Caramuru”: marcha by Antônio Nássara & Sá Roris. Recorded by Aracy de Almeida on 1 December 1938 and released on Victor 34402-A in January 1939.

- “Eu Não Te Dou a Chupeta”: marcha by Silvino Neto & Plínio Bretas. Recorded by Irmãs Pagãs on 4 January 1939 and released on Columbia 55.014-A in February 1939. It was a reference to the famous marcha “Mamãe, Eu Quero” (Vicente Paiva/Jararaca), recorded by Jararaca and released on Odeon 11449-A for the 1937 carnaval.

= = =

My thanks go to the collector Dijalma M. Candido, who contributed recordings, label images, and lyrics.

Copyright © 2003–2020 Daniella Thompson. All rights reserved.