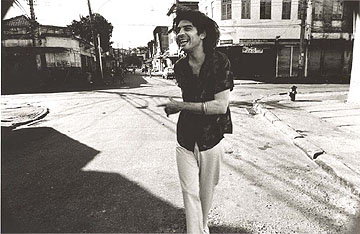

A quintessential carioca

Marcos Sacramento in his element.

June 1999

Photo: André Vilaron

Botequins

The botequim (or boteco) is a carioca phenomenon. All Brazilian cities have bars aplenty, but only Rio has botequins. The great carioca poet and composer Noel Rosa immortalized this institution in his humorous samba “Conversa de Botequim,” in which an impertinent customer commands a beleaguered waiter to bring him food, drink, napkin, pen, paper, envelope, cigarette, and ashtray; to shut the door; find out the football results; make a phone call on his behalf; and even to lend him money. The phone number mentioned in the song, 34-4333, is so deeply ingrained in the collective Brazilian memory that the Rio newspaper O Globo has appropriated it for its classified section, with one additional digit in the prefix (534) to allow for the passage of time.

Noel died in 1937. In the botequins of today you’ll seldom see a waiter; customers step up to the counter and get their own beer. Some of these storefront establishments are nothing more than holes in the wall, with a couple of tables on the sidewalk or not even that.

The singer Marcos Sacramento is a great conhecedor (expert) of botequins. As we amble through the town, he points out the beautiful old ones that have retained their original bottle shelves and cabinetry, the primitive ones with nothing but a counter, the tiny ones, the wildly painted ones. He tells stories and writes songs about the people who work behind the counters. Marcos also likes to drink beer—Brazilian beer that I, accustomed to English- and German-style brews, find watery and tasteless, particularly in this temperate autumnal climate. But happily, one can find beauty in botequins even without drinking beer. I ask Marcos to write an essay about botequins for the benefit of non-Brazilians. He just might do it (although, being a carioca, he just might not).

Note: Since this vignette was published, Marcos Sacramento has become a teetotaller.

The Marcos Sacramento fan club

No adult likes to admit to being a groupie, but I’m visiting Rio to meet my idol. It’s therefore a relief when another adult whom I greatly admire, the poet and lyricist Sergio Natureza, tells me: “Marcos is one of the greatest singers of this century. He’s my idol and he doesn’t know it.” Soon I find that I’m but a Johnny-come-lately, the greenest recruit in a select fan club that includes the music critic and historian Sérgio Cabral (who declared after hearing Sacramento for the first time: “Finally, a singer!”); the eminent music collector, researcher, and producer Paulo Cesar de Andrade (who lured Sacramento out of rock and into classic samba); the composer Paulo Baiano (who says, “Marcos is the best singer in Brazil, and I’ve known it for twenty years.”); and just about anyone who has the good fortune to be around while Sacramento employs his seductive timbre.

If you know him, the opportunities are many, as he bursts into spontaneous song at the drop of a hat: at parties, in the car, walking in the street. He knows the lyrics of countless old sambas, valsas, and marchas. He breaks into Stevie Wonder songs, Cole Porter songs, French chansons, Italian opera, old TV program jingles, and Carnaval tunes from his childhood. He imitates Ademilde Fonseca, Aracy de Almeida, and Linda Batista. He improvises hilarious Spanish versions of Brazilian songs. He intones “Segura o Tchan” in the styles of Caetano Veloso, Maria Bethânia, and Nana Caymmi. We’re transfixed by his voice and charisma. He’s shy and doesn’t even notice.

Rehearsal

The Lira Carioca ensemble is meeting to rehearse its next show, which will be devoted to songs from the 1920s, many of them never recorded. The repertoire was selected by the music researcher and pianist Fernando Sandroni, founder of the ensemble. The Sandronis are a distinguished family, offspring of an important newspaperman. They’re also a musical family. Fernando’s niece is the singer Clara Sandroni. Clara’s brother Carlos is a songwriter.

Lira Carioca’s previous show and disc were devoted to the works of Sinhô, “o Rei do Samba”—also from the ’20s. They’re just beginning to learn the new repertoire. The rehearsal takes place at Sandroni’s elegant house in Gávea. The musicians make a ragtag appearance amidst the Chinese porcelains and the burnished woods. With pauses for coffee and cake, they run through a number of songs I’ve never heard. The instruments are piano, flute, cavaquinho, and contrabass—the drummer isn’t here tonight. The voices are a soprano (Clara) and a tenor (Sacramento).

Eventually they perform a song I know: the gorgeous “Linda Flor” (Ai Ioiô) by Henrique Vogeler, Luiz Peixoto and Marques Porto, recorded by Isaura Garcia (1944), Elizeth Cardoso (1956), and Maria Bethânia (1990)—the latter in a tender duet with João Gilberto. Then the group launches into a delightful bit of fluff by Ary Barroso and Lamartine Babo called “Oh!...Nina!...” from the 1927 musical revue Ouro à Beça. I tell Fernando that Sérgio Cabral doesn’t mention this song in his book on Ary Barroso. Fernando says, “Cabral didn’t know about it—I told him.” Ary was barely 24 when he composed this catchy tune, and lyricist Lamartine was two months younger. Fernando is kind enough to write out the lyrics for me:

Oh!...Nina!... [foxtrot]

(Ary Barroso/Lamartine Babo; 1927)[Voice]

Nina era uma pequena

Levada demais

Flertes tinha uma centena

Com qualquer rapaz...

Sempre flertou

Sempre brincou...

Nunca se apaixonou...[Refrain]

Oh! Nina

Cuidado...

De fitas

Tu tens

Um punhado...

Oh! Nina

És fina...

Porém

Alguém

Te enganou...

De tanto namorar

Achaste o teu bem

Dentro do coração...

Oh! Nina...

Que sina!

Oh! Nina!

Chorares

Amares

Em vão!...

Copyright © 1999–2008 Daniella Thompson. All rights reserved.